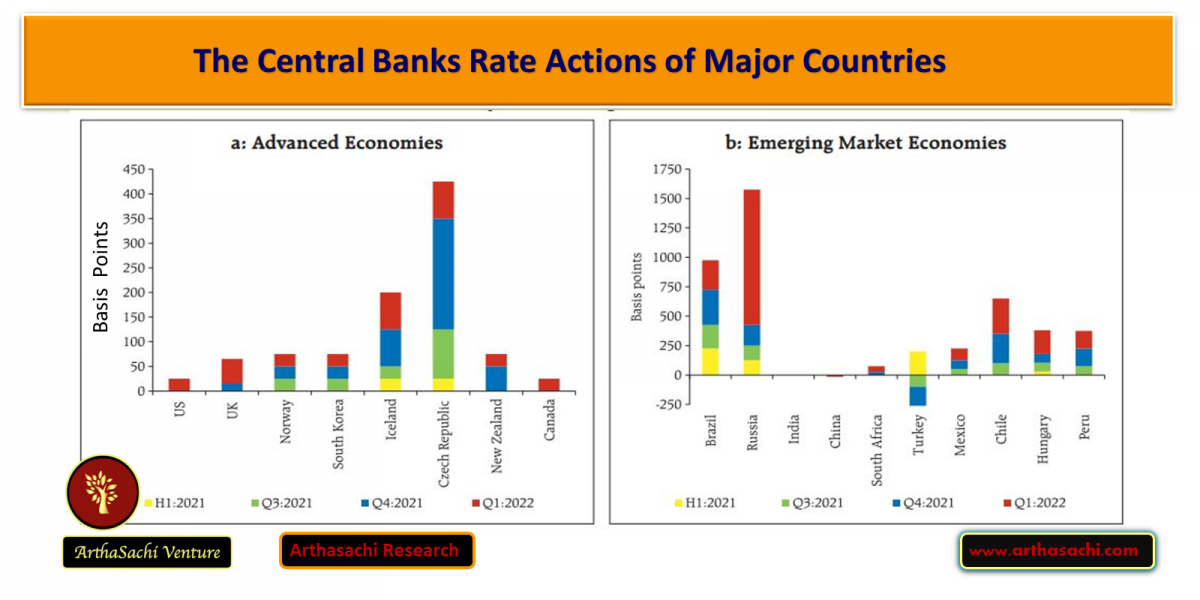

INTEREST RATE HIKE: The Central Banks Rate Actions of Major Countries

We tried to analyze the action of the Central Banks of the Major Countries in the recent past and how many of them are following the path of Federal Reserve.

Federal Reserve

In the US, the Fed began tapering monthly asset purchases of US$120 billion in mid-November 2021 and wound-up purchases in four months. In its January meeting, the Fed issued a set of principles for reducing the size of its balance sheet: (i) target range for the federal funds rate would be the primary means of adjusting the stance of monetary policy; (ii) reduction in balance sheet size would commence after a lift-off of interest rates; (iii) size of holdings would go down by adjusting the amount of re[1]investment of maturing securities; (iv) to eventually hold quantum of securities as needed to implement monetary policy efficiently and effectively in an ample reserves regime; and (v) to eventually hold primarily Treasury securities. In its March 2022 meeting, Fed raised the target range for the Federal Funds rate by 25 bps to 0.25-0.5 per cent, the first rate hike since December 2018. To operationalise the rate hike, the Fed revised up the interest rates on reserve balance and overnight reverse repurchase agreement by 25 bps each to 0.4 per cent and 0.3 per cent, respectively. According to the Summary of Economic Projections released in March 2022, the majority of FOMC participants expect interest rate to be 1.75-2.0 per cent by end-2022, i.e., a further 150 bps hike this year.

The European Central Bank

In its October meeting, the ECB announced a slower pace of asset purchases under the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) in Q4:2021 than in the previous two quarters. In December, it further reduced the pace of purchases for Q1:2022 and announced discontinuation of PEPP at end[1]March 2022 but extended the reinvestment horizon by one year at least until end-2024. To smoothen the transition from end of PEPP purchases, the ECB announced doubling of monthly purchase under the Asset Purchase Programme (APP) to 40 billion (approximately US$45.3 billion)3 in Q2:2022, to gradually revert to 20 billion (approximately US$22.7 billion) by October 2022.

In its March meeting, the ECB lowered the monthly purchases under APP from 40 billion (approximately US$43.9 billion) in each month of the quarter to a reduced schedule of 40 billion in April, 30 billion (approximately US$33 billion) in May and 20 billion (approximately US$22 billion) in June and announced end of APP purchases in Q3:2022.

The Bank of England

The Bank of England (BoE) maintained a pause on its policy rate in its November meeting. In December 2021, it raised the Bank Rate by 15 bps and in February by another 25 bps. Also, in keeping with the guidance of its August 2021 MPR, the BoE announced that it would stop re-investing for its maturing stock of government bonds. It would begin selling from its portfolio of government bonds only after the Bank Rate reaches 1 per cent, conditional on economic circumstances at that time. The BoE also announced that it would stop re-investing for maturing corporate bonds and that it would initiate a programme of corporate bond sales to be completed not earlier than end-2023. In March 2022, the BoE raised the Bank Rate by a further 25 bps to 0.75 per cent, suggesting that further modest tightening would be appropriate in the coming months.

Bank of Japan

In its December meeting, BoJ extended the Special Program to Support Financing in Response to the Novel Coronavirus by six months until end- September 2022. It also signalled the completion of additional purchases of commercial paper and corporate bonds by end-March 2022 and reversion to the pre-pandemic quantum of purchases from April 2022. In its March meeting, the BoJ said that inflation is likely to remain in positive territory for some time but maintained an overall dovish stance.

The Reserve Bank of Australia

Among other AE central banks, the Reserve Bank of Australia discontinued its yield curve control policy in November 2021 and halted weekly bond purchases in early February 2022.

The Bank of Canada

The Bank of Canada ended its weekly bond-buying programme in October 2021 and raised rate by 25 bps in March 2022 to 0.5 per cent.

The Bank of Korea

The Bank of Korea raised rates in November 2021 and January 2022 by 25 bps each to 1.25 per cent.

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand has cumulatively increased its policy rate by 75 bps since October 2021, taking it up to 1.0 per cent in February 2022.

The People’s Bank of China

On the other hand, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) effected a 50 bps cut in the reserve requirement ratio from December 15, 2021, which injected 1.2 trillion yuan (approximately $188.3 billion) liquidity into the economy. The PBoC also initiated a monetary policy easing cycle by reducing the 1-year Loan Prime Rate (LPR) by 5 bps in December, followed by a 10 bps cut in January 2022, supported by a 5 bps reduction in the 5-year LPR and 10 bps reductions in the interest rate on 1-year medium-term lending facility loans and 7-day reverse repurchase agreements. Since then, the PBoC has maintained a pause.

The Banco Central do Brazil

In contrast, most other EME central banks continued with policy tightening in Q4:2021 and into Q1:2022. The Banco Central do Brazil (BCB) effected three consecutive 150 bps hike in October 2021, December 2021 and February 2022 and a 100 bps hike in March, thereby, raising the Selic rate to 11.75 per cent.

The South African Reserve Bank

The South African Reserve Bank raised its policy rate by 25 bps in November 2021 – first hike in three years – and followed it up with two more 25 bps hikes in January and March 2022, taking the policy rate to 4.25 per cent.

The Bank of Russia

The Bank of Russia (BoR) had raised its key rate by 275 bps in three steps between October 2021 and early February 2022 on heightening inflation concerns. On February 28, 2022, in an emergency move, the BoR increased its key rate by 10.5 percentage points to 20 per cent to compensate for a sharp rouble depreciation and inflation risks amidst the geopolitical upheaval. It also undertook unbound fine-tuning operations to meet all liquidity needs of the banking system, besides other measures to shore up liquidity and the financial markets. As the structural liquidity deficit in the banking system continued to build, the BoR reduced the reserve requirement for banks to 2 per cent, releasing 2.7 trillion rouble (approximately US$26 billion) liquidity. The sanctions have precluded BoR’s access to its currency reserves in dollar and euros. Moreover, exclusion of major Russian banks from the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications (SWIFT) would affect financial transactions with the rest of the world. The BoR maintained a pause on policy rate in its March meeting but announced purchase of government bonds to limit financial stability risks.

Banco de México

Banco de México hiked its policy rate in two steps for a total of 75 bps in Q4:2021 and by another 100 bps in Q1:2022 through 50 bps hikes each in February and March, taking the benchmark rate to 6.5 per cent. The central banks of Chile, Peru and Hungary continued their monetary tightening. The central bank of Turkey, on the other hand, followed up the 100 bps reduction in key rate in September with cuts of 200 bps in October and 100 bps each in November and December. It has, however, maintained a pause in 2022 so far, with its benchmark interest rate at 14 per cent. To normalise excess liquidity conditions, Bank Indonesia began a 300 bps increase in domestic currency reserve requirement for commercial banks in three steps from March to September 2022.

Top News

Other News

MARKETS

WEALTH

ECONOMICS

START UP

TECHNOLOGY

BUSINESS

Alliances and Partners

Arthasachi Venture Footprints